In last week’s Austin Chronicle, Arts Editor Robert Faires wrote a fine piece about political theatre in Austin, “

Getting Political With The Tree Play and Robin Hood: An Elegy: Two new Austin plays tackle timely subjects.”

For those of you with the stamina, below are my uncut written answers to Faires’ questions about my take on political theatre, why this play now and where

The Tree Play fits into my body of work.

Robert Faires: You're not shy about calling

The Tree Play agitprop. Given how nervous some theatre folks get about political themes scaring away audiences, why are you so up-front about it? Do you have faith that Austin audiences will seek out plays with political messages, or are you doing it more out of a conviction that the message needs to be delivered and you don't want to sugar-coat it?

Robi Polgar: Well, it’s “an agitprop folk tale,” because I can’t just call a play a play, can I? Consider that my play about coal miners, the Great Depression and Thatcherism,

The Road to Wigan Pier, had the sub-title, “A (Socialist) Tea-Time Travelogue & Historical Musical Revue.” I can’t help myself. It’s a way of hinting at the experience to come. And hopefully you read that, or “agitprop folk tale,” and are just the littlest bit more curious about what going to that sort of performance entails. And it’s my way of not taking myself too seriously despite the serious subject.

But you are right. It’s “agitprop” because of course there’s an agenda wrapped inside the storytelling. And, yes, I’ve never been shy about calling attention to the political aspects of my work. There’s a message in this piece and audiences can expect to see a style of theatre that’s a shade different from how a straight drama might deal with this subject, where they can sit anonymous in the dark. I’ve always staged plays where theatre-goers bear a little more responsibility for their presence. Nothing intrusive; but you’re more than observer at

The Tree Play. You’re a witness. You’re sitting in the forest amongst the trees — it’s just out of the ordinary enough that maybe it’ll affect you unexpectedly. Maybe what you experience will alter your perception just a little.

Stylistically, agitprop conjures images of rough theatre, theatre that prizes raw materials over the polished. Calling the play an agitprop folk tale gives us leeway (or I think it does!) to create an experience that moves beyond the familiar to get our message across. The story is simple, the action is simple, the designs and movement are evocative. It’s not realistic, even as it relates realistic events. It almost sounds like a children’s theatre piece — that’s the “folk tale”-ness — except that there’s a level of sophistication that transcends it being a play for young people (that’s the intention, anyway). Despite the surface simplicity, it’s a bit of a challenge.

I’m not nervous about staging plays with overt political — or in this case activist — subject matter. I think audiences will seek out a good story no matter the content. Austin audiences are sharp. Give them the opportunity to experience art that treats them as intelligent, intrepid and open-minded and they’ll seek out those projects. And I am keenly aware that the audience has to have what John McGrath called “A Good Night Out” when they’re confronting big questions set before them (like three feet in front of them!). They have to have a good time. I have my point of view, of course; I know what outcomes I’d like to see. The play should be a little more open, poetic. Plus, there’s a good argument to be made that the real story of

The Tree Play is a love story.

Anyway, why would anyone shy away from a good political drama (or comedy)? The best political plays don’t push a point of view, which I find strident and off-putting. The best political plays engage audiences with compelling characters who struggle to resolve the seemingly unresolvable. Confronting issues of the day can make for satisfying drama. But you can’t push an agenda on anyone because that’s disrespectful. A good political drama presents the issue, shows the characters struggling with it and gives the audience opportunities to consider where they stand. Sometimes it asks them what they might do to improve the world. I hate in-my-face polemics. But I love a good piece of theatre that makes me reconsider my concept of the world, especially when it’s done in a way that’s peopled with interesting characters and that tells a good story in unexpected ways. And that probably makes me laugh or amazes me.

Most political theatre preaches to the converted. As a vehicle for getting a message out theatre has a short reach, unlike books, film, television, the Internet. But it’s visceral in ways other media can’t match. I’m drawn to that interaction between a group of people sharing a space with a group of performers telling a story. Maybe experiencing this play will influence our audience to take some sort of positive action, no matter how small.

RF: Why this play now? Was there something that sparked this particular story or the way you wanted to tell it? Is this a story you could have told 15 years ago, or 5? What do you think will resonate with an Austin audience today?

RP: Why this play now? Sadly it’s years and years too late. Decades, probably. On the other hand, it’s a call to action, right now: an imperative as timely as anything. It’s never too late to take a stand, either to save the rainforest or, more broadly, to confront any number of challenges society faces. We are the agents of our own destruction, humans. Well, some humans. It’s despicable how people in power can be so short-sighted as to mortgage our world for their (or their enablers’) profit. And while it’s also true that most of us sit idly, ignorantly, by and let this happen (bread and circuses, anyone?), it doesn’t have to be like that.

I’d like people to leave the play encouraged to think even a little about the rainforest; how it is a crucial and irreplaceable element of the way the Earth breathes.

The Tree Play says: it’s not late to do something. Become more aware, make informed decisions how you live your life. Make an incremental shift toward better stewardship of the planet. It’s not hard. We stop the breath of the rainforest with catastrophic consequences.

The spark for

The Tree Play was a piece in The New Yorker by Jon Lee Anderson, “

Murder in the Amazon.” It pushed all my buttons. The state working against its people for the benefit of big agribusiness. Hit lists of pro-environment activists, peasants, businessmen. A class struggle that also pit neighbor against neighbor. The profound selfishness of it all. The waste of nature and of human life.

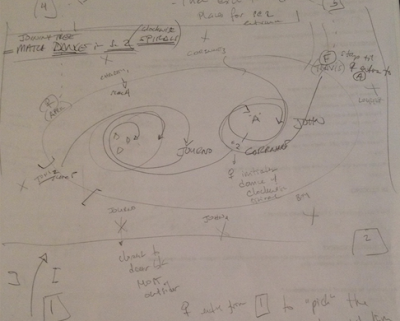

Reading the piece, an image came to me so I pulled out a spiral binder and started to write. I had a first draft in a week. Right from the start

The Tree Play was a “play with movement”; it was as important to create physical interaction between the humans and the forest that surrounds them as it was to tell the story of the wanton felling of the trees. I wanted the characters and the trees to dance together. And I wanted the audience to sit “in the forest” somehow.

Could I have told this story five, 15 years ago? I know I could have told this story five years ago because that’s how long it’s taken me to get it from the first draft to opening night! Okay, four years, so I’m ahead of schedule. But 15 years? Fifteen years ago I felt the same disgust for what was happening to the rainforest and its defenders, though had I written something to get a theatre audience to confront the issue it would have been a much different play.

My way into telling this story was through the character of a girl who grows up in the forest then returns to protect it. Why choose her? Or maybe I should ask, why did she choose me? Nineteen years of fatherhood certainly influenced my storytelling. Nothing like watching your kids grow up to reboot your sense of having to take responsibility for your world! Generational wisdom flows through the story as characters teach one another about life in the rainforest. It’s in the relationships between the girl and her father, the girl and the other men in her lives and, especially, between the girl and a particular tree, for which time is immeasurable, until it connects with the girl.

RF: How does

The Tree Play relate to other artistic work of yours that's had a political dimension? Where does it fit on your personal continuum of political work, theatrical or otherwise? And what about it is new for you, where are you trying something that you haven't before?

RP: I’ve always gravitated toward creating work that has a political dimension: in the plays or songs I’ve written or how I’ve chosen to approach plays I’ve directed. I’m compelled to find ways to challenge audiences to think about big questions, that take us beyond our daily lives.

The continuum, as you call it, is evident right from the start. Of the plays I’ve written and directed, the first was an adaptation of Klaus Mann’s “Mephisto” (1988), which traced one actor’s rise to stardom in Nazi Germany at the expense of every person he’d ever loved. I cast a dozen actors who played dozens of roles. They wore increasingly grotesque masks as their society spun out of control. I wrote original songs for the show. We danced. There’s a direct connection between that first effort and

The Road to Wigan Pier (2004), where a cast of a dozen actors portrayed dozens of characters whose lives were spinning out of control due to societal and historical forces they couldn’t contend with. I wrote original songs for the show. We danced. Oh, yeah, and there was a soccer match. And tea. Lots of tea.

Wigan had the advantage of being much more amusing than

Mephisto, which I put down to growing up and taking myself less seriously. Plus it’s a lot harder to crack jokes about Nazi Germany.

That said,

The Tree Play is lot like

Burnt (1995), a play about the rise of Nazism juxtaposed against modern-day intolerance, which I co-wrote with Catherine Rogers.

Burnt intertwined multiple modes of storytelling. There was the naturalistic story of a family trying to survive as their society turned against them in the 1930s; there were the dream-like movement sequences that evoked the Jews’ journey from ghetto to boxcar to concentration camp; and there were madcap scenes that poked fun of the Nazis and their methods: We reduced the Wannsee Conference to a game show that had audiences struggling not to laugh — we were talking about exterminating a whole ethnic group after all, but it was funny.

The Tree Play also uses short, naturalistic scenes interspersed with passages of evocative movement to tell our story of a girl who grows up in the rainforest, then returns after she has become an environmental activist. And like all my work, we’re finding ways to bring the audience into the environment, into the story.

That’s something else that’s imbued my idea of theatre making: finding ways to create a sense of shared space so the audience isn’t watching from some safe remove but senses it has a part to play, even if it’s only pretending to be going out for a night at the local working men’s club (

Wigan Pier) or perched in a gallery above the circus (

Life of Galileo; 1998) or looking out from under the Romanesque arches of 15th century Venice (

Scenes from an Execution; 1995) or sitting on the beach watching a clown show about World War I (

Oh, What a Lovely War! 1992). With

The Tree Play the idea is to lead audiences into the rainforest to experience more viscerally issues of deforestation and climate change through what I hope is a touching story of a girl and a tree.

What’s new for me? Well a lot of this process feels new because I’ve been away from making theatre for a decade! It’s been equal parts exhilarating, exhausting and downright stressful producing a play for the first time in so long.

Given all the years I’ve written and directed (I think of directing as a facet of creative writing — a process of conception, creation, adaptation, editing) this is actually the first time I’ve penned the entire script myself.

I’m also taking more responsibility for the choreography of the piece, thankfully with the help of the inestimable, wonderful Toni Bravo. We held an audition-free casting process. Instead of having actors read for roles, we held a series of workshops that focused mostly on movement. We experimented with the ensemble-as-chorus but did practically no scene work to speak of. It’s a leap to start a process and not revert to the tried and true. Instead we trusted that the workshoppers who played together well were the best actors to cast across a range of speaking roles, unheard, and I’m delighted it’s turned out that way (and save for one actor I worked with 10 years ago, this is a cast I’ve never worked with nor seen on stage before).

One other unusual thing for a play I’m working on:

The Tree Play is short!